Okay, bye

Originally published April 9, 2014 in El Estoque.

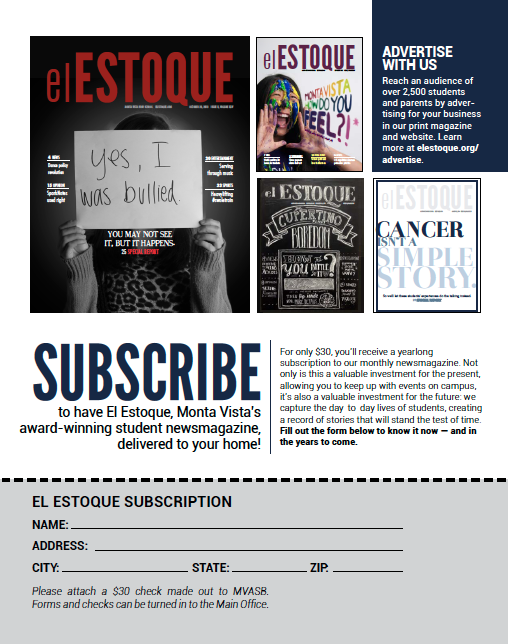

I’m writing this letter — my final letter — on the last Saturday of March. (Today is Wednesday, April 9.) Let me be honest with you: right now, this magazine is in pretty bad shape. The majority of stories are not yet complete. Few pages have a design planned out. And due to some recent and shocking financial revelations, we may or may not have enough money to even print this issue.

There’s a quote from Nelson Mandela that I think is pretty accurate: “It always seems impossible until it’s done.”

Mandela’s words do a nice job of summing up my experience on this journalism staff both for the last three years and during my time as editor-in-chief. (They also sum up my entire high school experience quite neatly, but that’s a story for another time.) The tasks we’ve assigned ourselves this year — build a new website, expose and fight bullying on our campus, finish a 40-page magazine by 9 p.m. Friday once each month — have often seemed insurmountable. But when it’s done, we ask ourselves, why did we ever doubt it would happen?

The best stories are like that, too. A perfect marriage of impossibility and inevitability. Think about your favorite book or movie or TV show. Then think about the stories this magazine has told over the past year: The quiet boy who found his voice through vlogging. The soccer player of small stature who played so well that he had been recruited to play for Stanford by the beginning of his junior year. The girl who fought cancer twice and won. Impossible. Inevitable. Symmetry so strange that it just makes sense.

I agree that journalists have a responsibility to serve as the watchdogs, to uncover the truth at all costs. But I also think that journalists have the responsibility to tell those symmetrical stories, the ones that are easy to write off as fluff — because those are the stories that inspire us and challenge us and show us what we’re capable of.

If you’re seeing this on Wednesday, April 9, then it means we finished the magazine. I hope you will find within its pages something of value — something that moves you, enthralls you, maybe even makes you think a little.

It seemed impossible, but now I’m done.

Okay, bye (design)

Table of Contents (Issue 7)

The Grain Remains

Originally published April 9, 2014 in El Estoque. Co-designed by Colin Ni.

Here are a few numbers (design)

Here are a few numbers

Originally published March 12, 2014 in El Estoque.

Here are a few numbers:

Of 161 surveyed students, 68 percent said that at least one of their relatives or friends has been diagnosed with cancer.

One in two men and one in three women will be diagnosed with cancer at some point in their lifetime.

When we sent an email to the student body asking whether anyone would be willing to share their experiences with cancer, x students came forward. And that’s only the number of students who opened up to us; there are no doubt countless others who continue to carry the weight of their experiences in silence.

These numbers are frightening and overwhelming. They reveal the prevalence of this disease, which we often fail to discuss outside the confines of biology classrooms, on our own campus. But these numbers are also reductive: There’s no way digits can capture how junior Nicholas Egan felt when his father succumbed to lung cancer in 2006, or how senior Emma Lewis felt when her friend passed away from Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia five years ago, or how junior Lavanya Rajpal feels every single day as she fights the cancer that has struck her for a second time.

Numbers are simple. Numbers are streamlined. But only stories can capture the complexities of our experiences.

We as a staff pride ourselves on being storytellers. We recognize that a well-told story is more than just words on a piece of paper, that it can be catharsis and therapy and unifier all at once. We recognize also that this — our special report on cancer at this school, which starts on page 25 —is one of the most important stories we’ve told.

In our staff editorial “Stronger Together,” on page 12, we propose the establishment of support groups for students struggling with issues such as cancer. When 68 percent of us are touched by cancer, why do we continue to suffer alone? We hope the stories we present here will serve as the first step in the process of forging a more connected student body. Our goal with this issue — and we recognize that this is a cliche — is to remind you that you are not alone.

Cliches came up a lot in our brainstorm for the cover of this magazine. We struggled trying to think of a string of words that would encapsulate what it means to go through cancer, or to have a loved one go through cancer. It seems obvious now that it was a futile task: You can’t distill something like that into a few syllables, just like you can’t distill something like that into a few numerals.

Cancer is not a simple story. These students’ experiences aren’t either.

Back page (Issue 6)

Such language! Very art! (Design)

Such language! Very art!

Originally published March 12, 2014 in El Estoque.

By now, you’ve probably seen doge. If you haven’t, quick explanation: Some folks on the Internet thought it would be funny and adorable to cover photographs of Shiba Inus with Comic Sans captions detailing the dogs’ internal monologues. The captions typically read something like, “Wow… Such amaze… Very caption.”

The meme, which is admittedly funny and adorable, has spread like Ellen’s Oscar selfie. On top of inspiring countless spin-offs (a quick Google search revealed Snoop Doge, Twinkie Doge and Windoge 7 among others) and a currency (Dogecoin, currently valued at a tenth of a U.S. cent), Doge has also influenced the way we speak in real life. I’ve heard phrases like “such amaze” spoken out loud in public. More embarrassingly, I’ve said them.

This phenomenon of Doge is representative of a larger shift toward text speak, which also includes abbreviations you’ve definitely heard of, like “LOL” and “OMG.” Forty percent of 161 students surveyed online by El Estoque said that they were somewhat familiar with text speak, and 30 percent said they were very familiar. Does this familiarity signal a shift toward pervasive (or, rather, more pervasive) teenage idiocy?

A common argument against the proliferation of slang is that it makes the speaker sound, well, stupid. Another is that it signals the death of English as we know it. Or, as Robert McCrum, associate editor of the British newspaper The Observer, put it: “It’s a coarse vulgarisation, and a reduction of the expressive capacity of the language.”

While you’re thinking about that, let’s take a break to talk about Shakespeare. According to the website shakespeare-online.com, the Bard invented over 1,700 words that are commonly used today by “changing verbs into adjectives, connecting words never before used together, adding prefixes and suffixes, and devising words wholly original.” This is almost identical to Merriam-Webster’s definition of slang, which reads, “an informal nonstandard vocabulary composed typically of coinages, arbitrarily changed words, and extravagant, forced, or facetious figures of speech.”

We would never call “Hamlet” or “Julius Caesar” a “coarse vulgarisation” of the English language — despite the fact that Shakespeare actually was a master of the sexual pun, thus literally utilizing “coarse vulgarisations” — so why do we treat Doge and “yolo” differently?

Okay, okay. Obviously “much wow” is not on the same intellectual level as “Soft! What light through yonder window breaks?” But there’s no denying that both modern slang and Shakespearean wordsmithing embody the same disregard for convention, the same spirit of invention.

So while teen speak may sound stupid, it may not actually be stupid. In fact, according to a 2005 article in The Observer, the quality of 16-year-olds’ writing had actually improved since 1980 despite the increase in the prevalence of slang. A two-year study at Cambridge University found that teenagers in 2004 — despite being 10 times more likely to use non-standard English and colloquialisms in exam papers than their 1980 counterparts — used stronger vocabulary and more complex sentence structures than in the past.

Such counterintuitive!

Katherine Barber, editor of the Canadian Oxford Dictionary, provided a possible explanation on oxfordlearning.com: “If the kids are picking up new words and new meanings then that means that they’re playing with the language.” In other words, our ability to invent and use slang signifies an understanding of English mechanics — it’s like modern art. In order to break the rules, we must first know how to use them. It’s a Shakespearean tendency, perhaps lacking in Shakespearean execution.

That being said, your teachers and future employers probably will not view your daring wordplay as particularly literary. It’s a good idea to restrict your usage of Internet slang to appropriate situations. But you don’t need to feel guilty for contributing to the destruction of the English language because you’re not.

You may sound like an idiot, but you’re actually on the cutting edge. Wow!